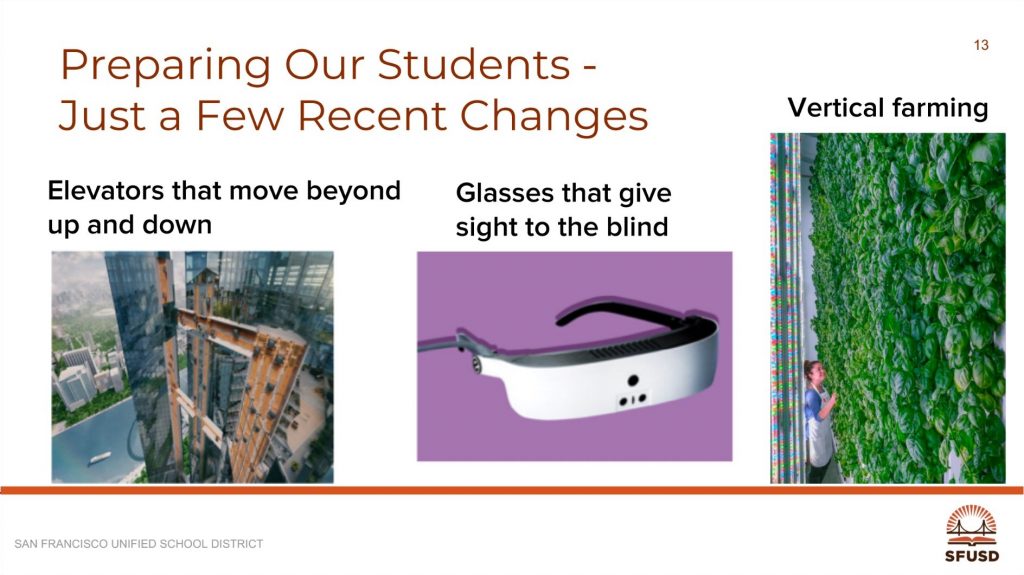

In his opening remarks at the annual San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) school site council planning summit, Superintendent Vincent Matthews, Ed.D. displayed the slide below. He explained that all the of these technologies had been developed in the last year, highlighting our need to ensure our students are prepared for a changing world

When I looked at the slide, however, I didn’t see new innovations. Instead, what I saw was the Wonkavator from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Geordi La Forge’s VISOR from Star Trek: The Next Generation, and a concept that I knew was familiar but which I couldn’t place at first. (A quick Google search turned up the Chlorella plantation, “a towering eighty-story structure like the office ‘In-and-Out’ baskets stacked up to the sky” from The Space Merchants by Frederik Pohl, circa 1952.)

I mention this, not to disparage Dr. Matthews’ reference to these “new” technologies and certainly not to disagree with his assertion that we must prepare our children for a future very different from the one we grew up in — an position I very much agree with — but instead to note that the future does not come solely from engineers and scientists but also from authors and artists.

In fact one could argue that all major advances come from the arts; scientists, technologists, and engineers merely implement those ideas.

Simon Lake, known as the father of the modern submarine, was inspired by Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Verne also inspired Igor Sikorsky, the man who developed the modern helicopter, with his novel Clipper of the Clouds, a tale of rivalry between lighter-than-air craft (dirigibles) and heavier-than-air helicopters. Robert Heinlein’s 1942 short story Waldo, about a man who invented remote controlled arms to compensate for his physical limitations, gave rise a few years later to the real thing, which now share their name with Heinlein’s story and its protagonist.

Martin Cooper credits Dick Tracy‘s wrist radio as his inspiration for the first mobile phone. He also credits Star Trek‘s communicator for the idea of voice dialing, saying “that was not fantasy to us … that was an objective.” Tom Swift was a prolific inventor; unfortunately he was also fictional. Jack Cover, however, was a real physicist who, after reading about Tom Swift and his Electric Rifle as a boy, invented the TASER — an acronym for Tom A. Swift Electric Rifle.

Mind you, it is not my intention to belittle the difficulty of bringing new ideas to life; figuring out how to create something in the real world is every bit as much an art as coming up with the idea in the first place.

What I do want to do, however, is emphasize the importance of supporting and encouraging children interested in the arts and ensuring that those whose interests are more technological still receive comprehensive exposure to the arts. We need to show children that their artistic creations are as valued as their scientific ones and that exposure to the arts means exposure to new ideas, many of which become real-life technological advances.

If we don’t, we run the risk of missing out on the real-world versions of all the other amazing innovations dreamt about by artists and brought to life by engineers.

This is why we need the “A” in STEAM.

Tags: art, arts, engineering, literature, math, mathematics, science, STEAM, STEM, technology